buffy acacia

If we take the short version of this story at face value, it goes something like this: “Once upon a time, men wore pocket watches. Then some clever watchmakers created movements small enough to fit into women’s jewelry. When World War I broke out, the men who fought , we realized that it was much more practical to wear it on the wrist. From that point on, the watch industry became what it is today.

Like all oversimplifications, there is a grain of truth in this, but the nuances contained in hundreds of years of history are completely lost. It ignores the pioneers who actually started wearing wristwatches first, and unfairly denigrates the early wristwatches for women. It also overlooks the importance of mass production and the development of new technology, without which it would have been impossible to surpass the bespoke watches of Renaissance royalty.

oldest known wristwatch

One of the first mental frameworks we need to do is accept that watches were never “invented” by anyone. Sure, there must have been a first time, but as soon as the parts were small enough, clocks became ubiquitous. Mechanical clocks were invented in Europe in the 12th and 13th centuries as a replacement for water clocks. Mesopotamian Ismail Al Jazari pushes the limits with miniature automata and robots During the Islamic Golden Age, portable watches were common by the 1450s (although they were still rare and exclusive to the elite). By the late 16th and 17th centuries, they became widespread.

As soon as watches were small enough to be worn, they were worn in every imaginable way. Hang it on a necklace or belt, or set it on your mirror. Even something as small as a ring. They are not always simple, time-only movements, but are usually characterized by some kind of repetitive complication. The first written record of what was most likely a wristwatch was a “bracelet” given to Queen Elizabeth I by Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, in 1571. Still, small clocks at the time were not considered high-precision devices. . Although technically complex and expected to be used as an astronomical tool, most people still used sundials to set their clocks until the invention of highly accurate pendulum clocks in the 1650s. I was there.

Clocks were not expected to be completely accurate, so wearing a watch on the wrist to tell the time was not a priority for many people. That’s especially true for royalty and aristocrats who are wealthy enough to actually own them. They don’t worry about being late for work or worrying about parking meters. Wristwatches have existed and been actively developed for up to 400 years, but it wasn’t until the 1800s that cultural and technological conditions made wristwatches popular.

Industrial revolution as a catalyst

So what changed from the 18th to the 19th century?First of all, there was the Industrial Revolution. Workshops became factories, peasants became labor forces, and small towns that had barely survived the Middle Ages suddenly expanded into cities. Industrial mining led to the gold rush and the discovery of valuable minerals, which injected wealth into corporations and created a new upper class completely separate from monarchy and aristocracy. The availability of steel enabled the spread of railways around the world, allowing people, culture, and technology to move more freely than ever before.

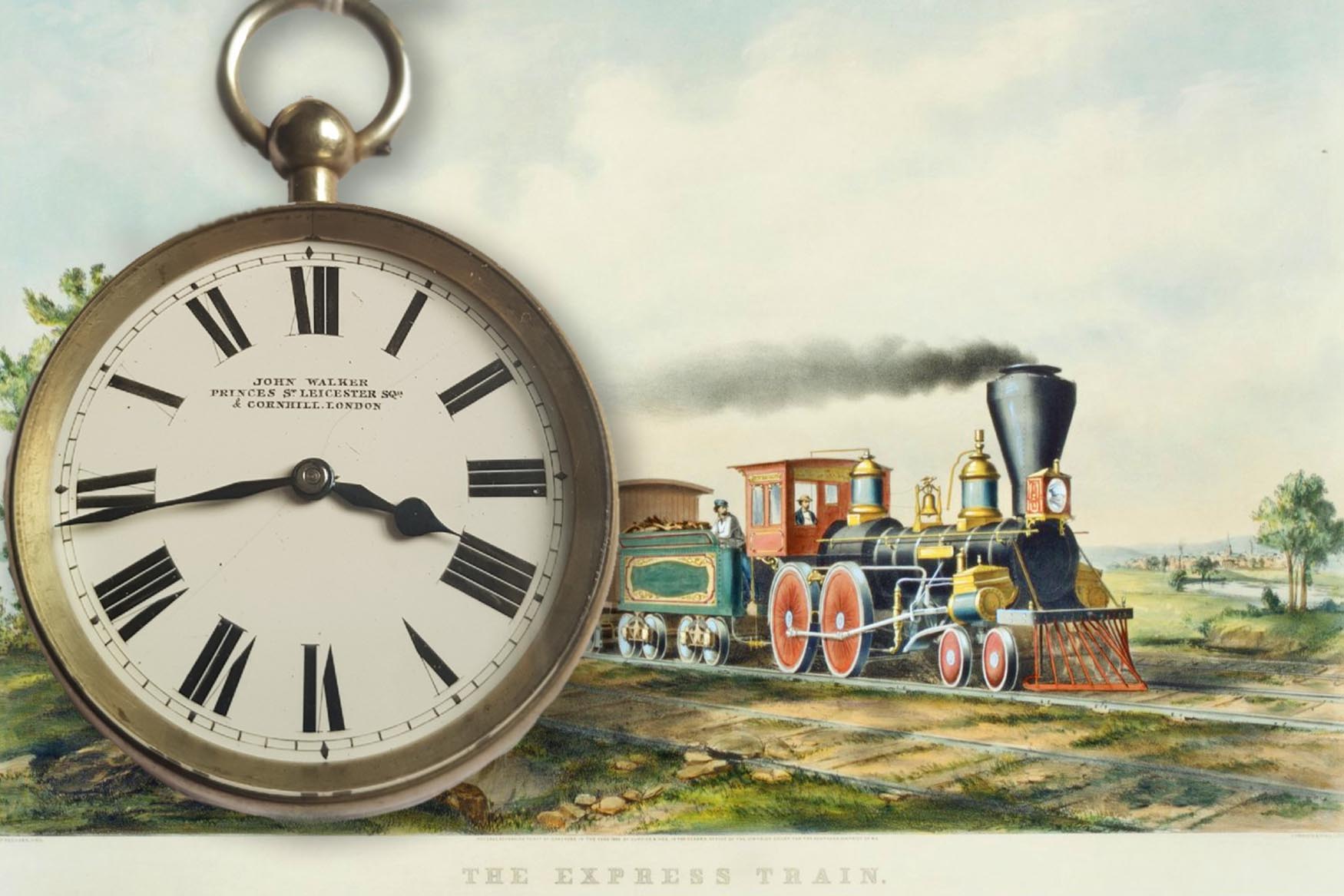

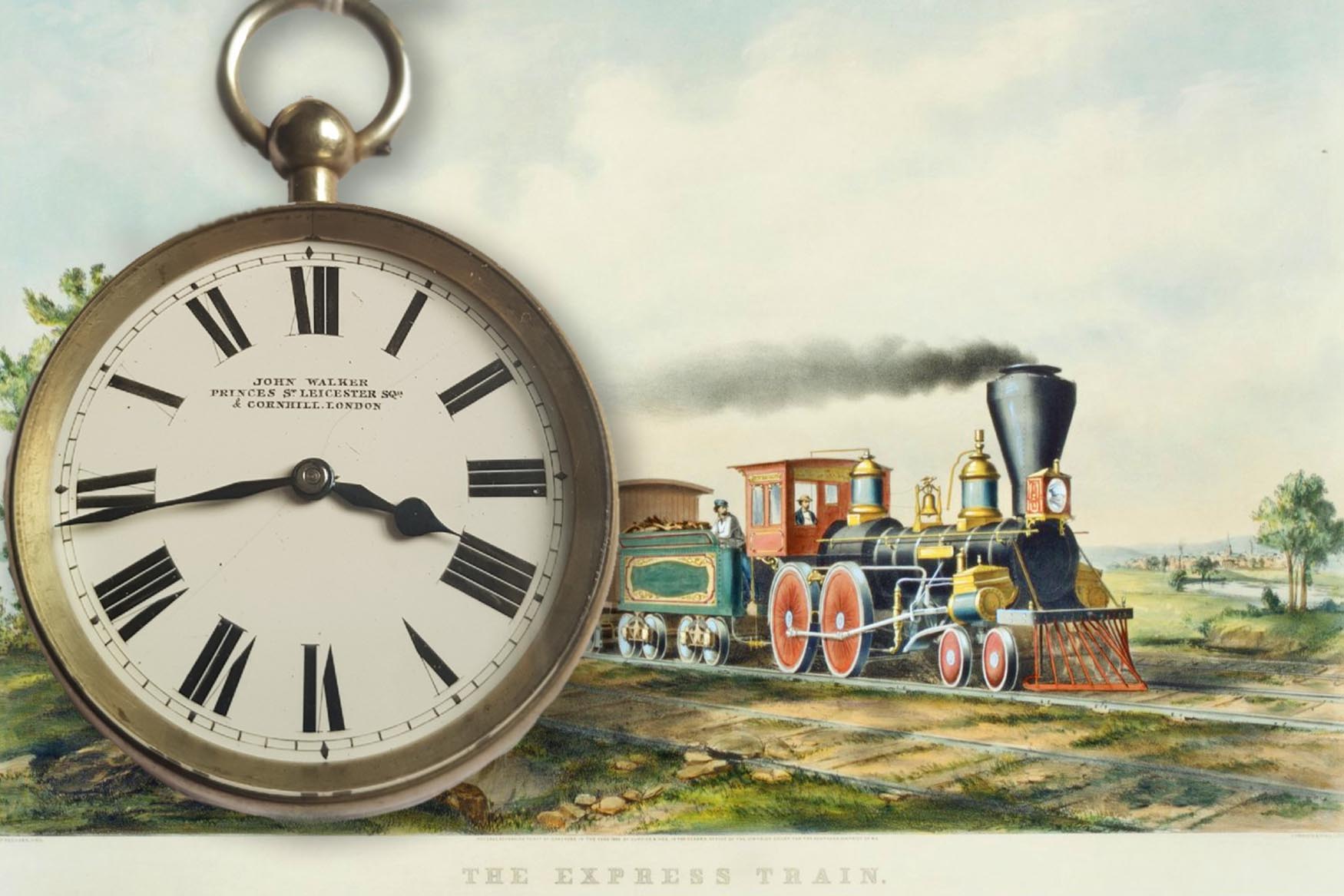

These changes have made watches available to more people, which is why pocket watches have become more popular. Movements made from machined brass can be produced relatively quickly on American-style assembly lines, and for an average wage you can even buy yourself a watch that looks like solid gold thanks to electroplating. But while the railway network enabled such commercialization to take place across the continent, the speed and efficiency of trains was fundamentally at odds with the world’s entire relationship to time.

How trains changed our perception of time

If you start walking at sunrise and follow the path of the sun until sunset, you will add about one minute to the length of the day. The horse-drawn carriage travels at about the same speed as us, but it is a little slower depending on the journey. Long before ordinary people had personal clocks, medieval towns had central clock towers based on measurements of the sun, with time differences naturally existing to reflect their longitude positions. I was there. For the average watch owner traveling between towns in the 1700s and 1800s, time differences were completely negligible and would probably have been masked by the pocket watch’s daily errors.

The train, which normally ran at 60 to 80 km/h, is about 15 times faster than us. Telegraph poles, popularized in the mid-1800s, allowed almost instantaneous communication across the country. What happens when two trains operating on slightly different timetables share a track between towns? They may end up crashing. What was once a natural occurrence for nearby towns to have their clocks shifted by just a few minutes has now become a grave responsibility with deadly consequences. After centuries of development as a maritime navigational tool, the chronometer needed to return to land for the simple purpose of keeping accurate time. But for these highly accurate pocket watches to make a difference, the towns themselves had to agree on standardized time.

Time zones worked by bringing all these towns and cities together under a single, unified time standard. Most countries use a constant time of Greenwich Mean Time plus or minus, and some large countries span multiple time zones. It was the railroads that demanded precision in mass-produced pocket watches, but only when combined with standardized time zones. This is not to say that precision was never important before, but it was only due to railways that we came to think of time as a fixed constant rather than a fluid, local dependence based on the sun. Thanks to a change in cognition. Time zones are one of the big steps towards globalization, making it easier for people to travel and do business abroad.

A watch that focuses on practicality rather than decoration.

Between 1450 and 1850, wristwatches were rare curiosities enjoyed primarily by the ruling class. Another example is Breguet wristwatch made for the Queen of Naples in 1810it is generally accepted to be the first “modern” wristwatch. The only reason watches weren’t more common is because, frankly, there was something more interesting about them from an artistic and astronomical point of view, and the wrist was a practical place to wear them. However, the clock itself was not yet a practical tool. The demand for precision thanks to the railways encouraged the development of movements’ resistance to shock, extreme temperatures, and durability. Ingress of water or moistureand finally magnetic Inspired by marine chronometry. When all this was in place, a practical wristwatch became actually possible for the first time.

Enter the wristlet. Around the 1880s, both women and men wore watches on their wrists, especially in the decades before World War I. Truly flamboyant examples of wealthy women wore ribbons tied around their wrists, and sometimes even various strings of pearls. Men’s fashion has worn more jewelry than women throughout history, but the abandonment of big men in the late 18th century led to a reduction in jewelry and color in favor of the modern lounge suit. The idea that wearing jewelry, even if it was functional, was eviscerating was well-established.

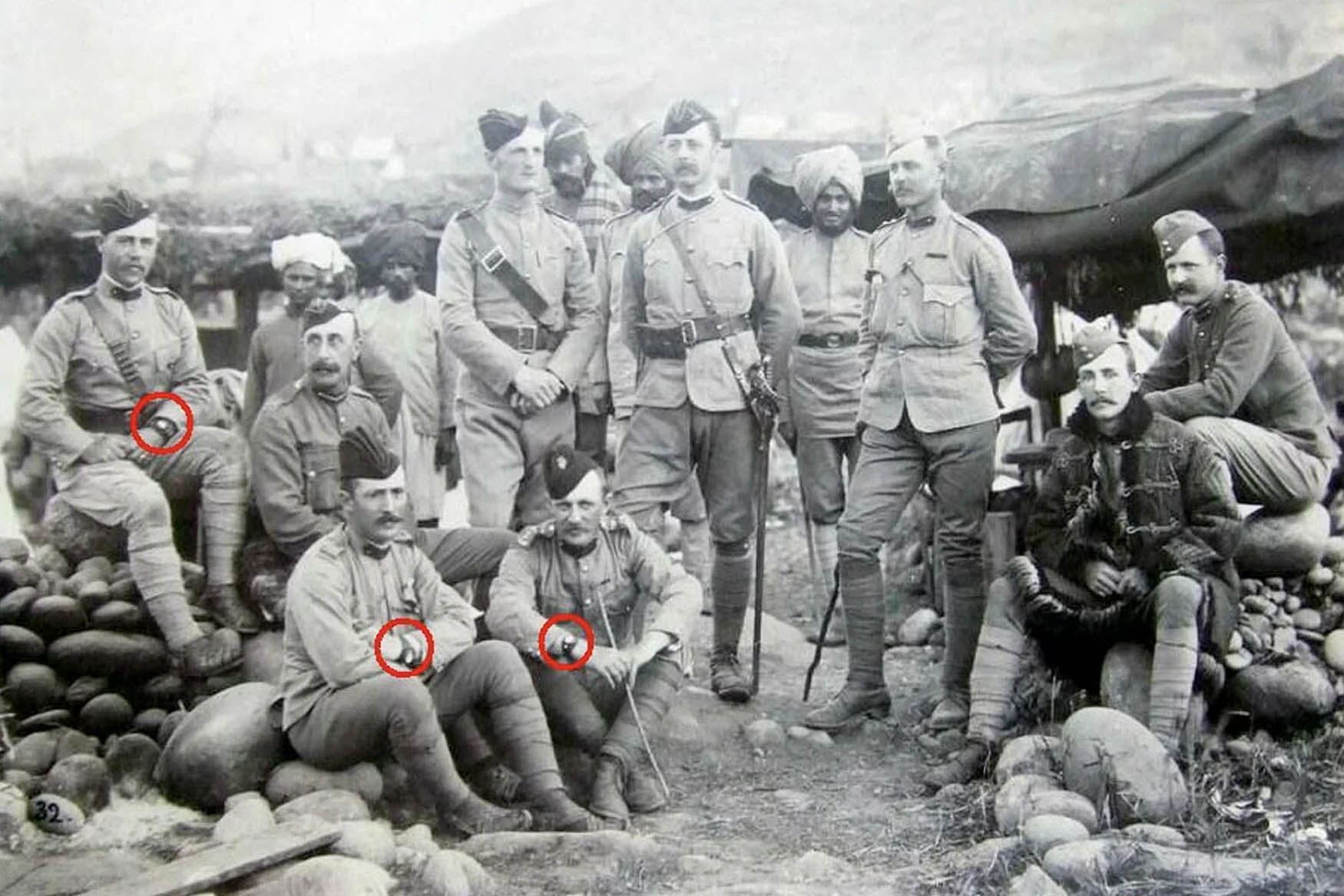

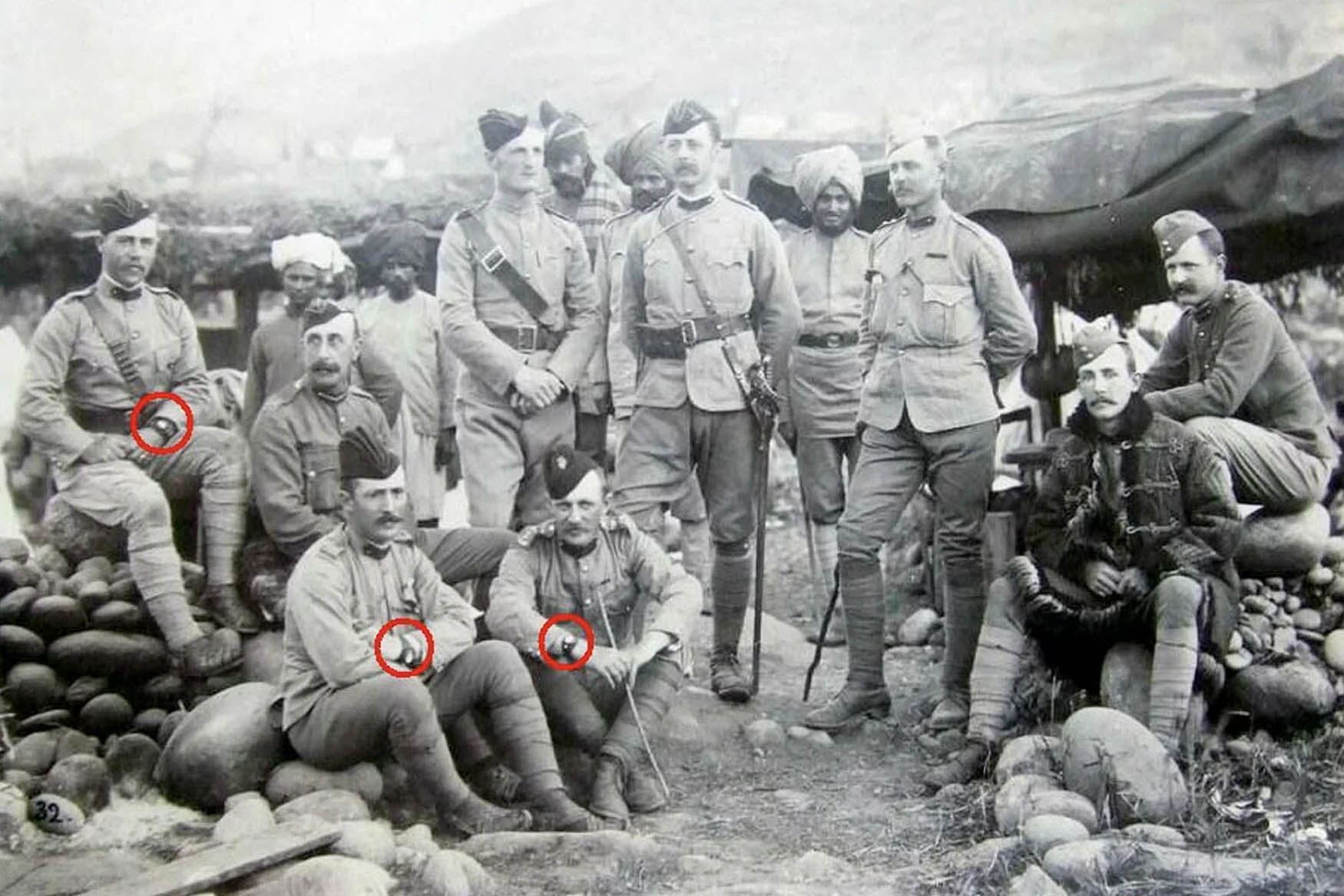

Still, men’s wristlets were used for those who needed them, regardless of lofty fashion critics. Wristlets for men were usually leather holders for small pocket watches; Same as band strapThese were also worn by women who could not afford fine jewelry. Leather straps not only keep the watch in a convenient location, but also add durability, making it the perfect watch for military personnel working outdoors. That’s exactly the method used in the British Hazara expedition of 1888, and many, if not all, of the men are photographed wearing it. The Cartier Santos Dumont was introduced to the public in 1911 and essentially marked the beginning of wristwatches as we know them today: practical and fashionable for both genders.

World War as a turning point

By the beginning of World War I, militaries across Europe had already recognized the practical advantages of wristwatches. The idea that wristwatches were invented during World War I is clearly false. Because now we are investigating how watches have existed for centuries. However, it was for soldiers in World War I that wristwatches began to be mass-produced. It shared many elements with pocket watches, such as a pebble-like case, an enamel dial, and in some cases being made of precious metals, but also included soldered wire lugs for inserting a strap, making it easier to wind up. A crown at 3 o’clock has been added to adjust the time. Large, easy-to-read Arabic numerals that can be set with the right hand Often filled with luminous (radium) paint.

By the end of World War I, the watch industry as we know it today was more or less fully established. Many of the same Swiss factories that made trench watches During peacetime, he explored a more decorative, art-based style.leads to Classic designs such as Jaeger-LeCoultre Reverso World War II completely cemented the world’s dependence on wristwatches, and Switzerland officially took over as the world’s number one watch nation, replacing the British, French and American establishments. It was at this time. Of course, development never stops. Events such as the quartz crisis It also played a major role in shaping the wristwatch in modern culture. But if you want to thank the person who conceptualized the watch on your wrist, you have to go much further back than the 20th century.