Buffy Acacia

Like almost all human technology, watches seem to have developed slowly at first and then all at once. Protecting watch mechanisms from dust and moisture is just common sense; otherwise, no one would make cases for watches. When pocket watches were popularized in the 1800s, people didn’t immediately think of the need to take these amazing miniature timepieces swimming. But when it came to the eventual development of dedicated diver’s watches in the 1950s and 1960s, there were two old companies that made this possible: Borgel and Taubert.

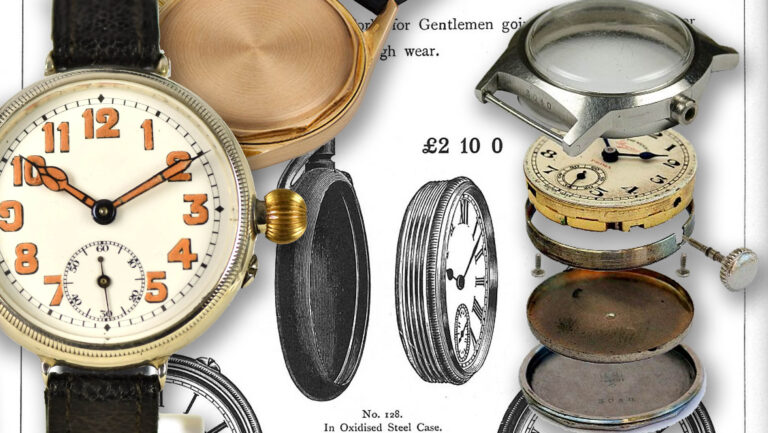

Imagine a time in the late 1870s when chronometers were in full operation on ships.The Challenger had only a few years ago discovered the deepest part of the ocean, the phonograph had just been invented, and the Balkans had been thoroughly reorganized after the Russo-Turkish War. Henry Morton Stanley had completed his trans-African expedition in 1877, and Western Europe was largely romanticizing the idea of roaming the jungle. Explorers who wanted to wear a wristwatch in such humid conditions could use a pocket watch with a canteen-shaped crown, essentially a cover threaded through a gap in the stem of the case and sealed with a leather washer.

These Explorer watches offered fairly primitive water resistance, but They laid the foundation for subsequent developmentsWhile you wouldn’t want to submerge your watch in water, this prevented a significant amount of moisture from getting inside the case and causing condensation and corrosion. The screw-down crown we know today was patented in 1881 by Ezra Fitch, who used the crown itself as a screw-down cover rather than a separate cover.

While this was a huge advance in terms of convenience and aesthetics, it didn’t necessarily make the watch more water-resistant. The same is true for modern watches: a screw-down crown prevents the crown from being accidentally opened underwater, but it doesn’t actively keep water out.

Over the next decade, various small improvements were made to the screw-down crown, but the next big leap came in 1891 thanks to François Vogel. Vogel’s patent described a two-piece pocket watch case that instantly eliminated half of a watch’s potential weaknesses when it came to water resistance. The movement was mounted on a carrier ring, to which the dial and crystal were also attached, and the whole thing was screwed into the front of the case. The threads were very fine, creating a tight seal against dust and moisture. For the crown, a split stem was used that allowed it to thread through both the case and the carrier ring. Rather than the screw-down crowns of the time, which collected dust and wore out surprisingly quickly, the crown assembly used a spring that pulled the crown down and maintained constant tension.

You might wonder How to ensure your watch is waterproof Some cases were gasket-less, but gasket options in the 1890s were waxed cotton, string, or leather. None of these materials were particularly good at keeping water out in the first place, so metal-to-metal contact was all the case needed, provided the manufacturing quality was high enough. There are even stories of Borgel cases accidentally being put in the washing machine with no problems. Of course, old-style “waterproofing” wasn’t intended for repeated swimming, so close tolerances were sufficient in most cases. Also, some cases were made from 18k gold, so they weren’t necessarily only considered sporty.

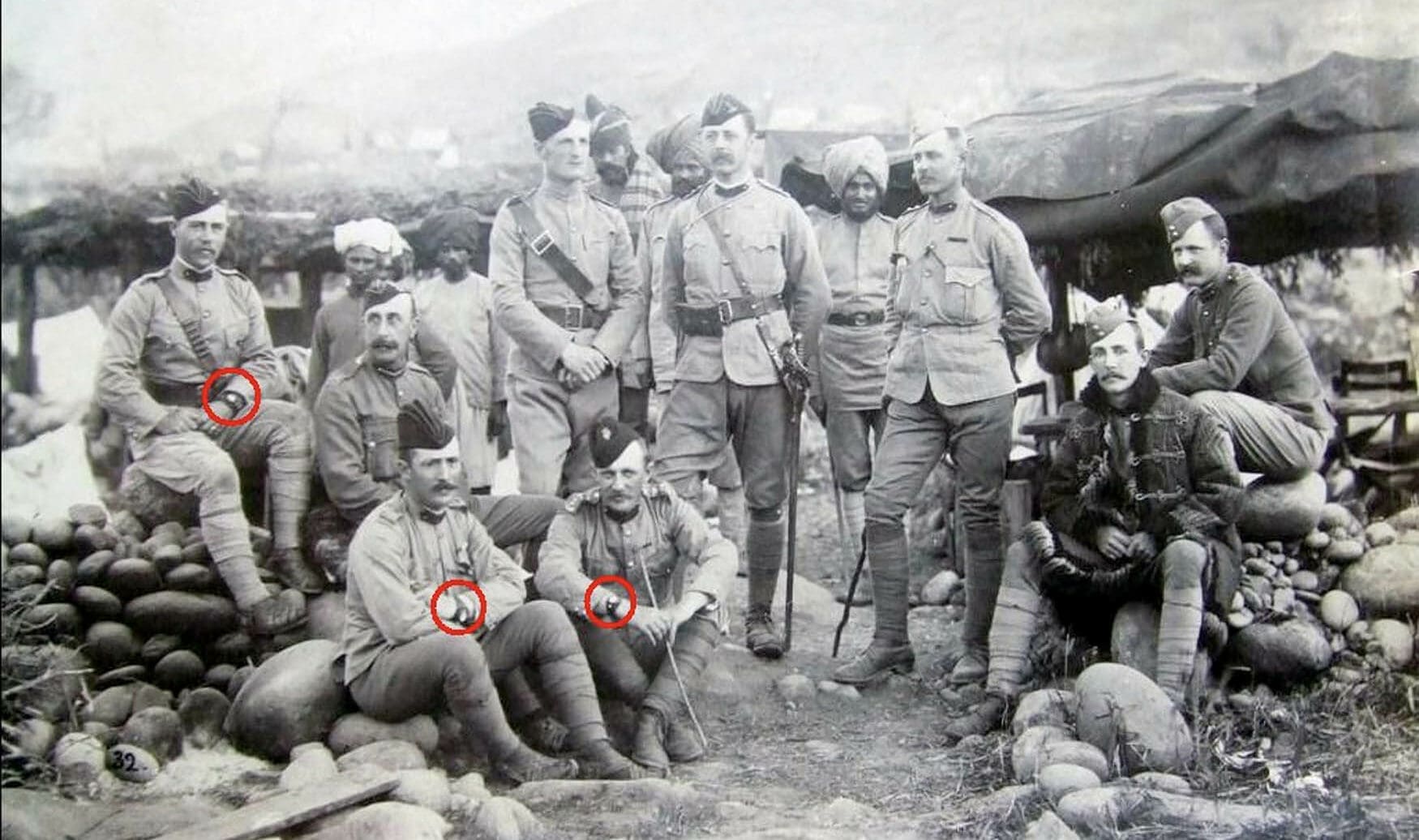

By the start of World War I, Vogel had incorporated his two-piece case design into smaller wristwatches. “Wristlets,” as they were then called, were rare but not unknown before the war. The oldest Vogel watch case was used in a one-of-a-kind watch made by IWC in 1906. More Vogel watch cases were produced as wristwatches were recognized as superior tools of war over pocket watches. Longines was also an important Vogel customer, especially during World War I.

After the First World War, things were not so good. François died in 1912 and his daughter Louisa Borgel took over during the war, but then sold the company to another Swiss family, the Tauberts. The newly founded Taubert & Fils owned and inherited Borgel in every sense of the word, but in a way that was worthy of the original legacy. You can also see that the new ruling family had the utmost respect for François Borgel, as they re-registered the FB trademark and keys. All Borger cases are engraved (Except for Mido Multifort watches) and continued into the 1960s.

Within a few years, Taubert filed a series of patents related to waterproofing, two of which are particularly noteworthy. The first was granted in 1928 and involved a new method of sealing the crown stem of a watch with natural cork. A special tool was used to compress a greased piece of cork, which was then inserted into the crown, where the cork expanded to fill the gap. Although a screw-down crown was not needed to prevent water ingress and was theoretically safer, daily manual winding quickly wore down the threads, especially in cases made of soft metals. The system was most famously used on the Mido Multifort from 1934 onwards, and was named Aquadura after the original patent expired in 1959. It’s only in the last decade or two that Mido has stopped using the Aquadura system, even after rubber gaskets became commonplace.

The second notable Taubert patent was for a decagonal case with a 10-sided screw-down bezel and caseback. To say it was ahead of its time would be an understatement: the flat sides of the new parts could be tightened with tools rather than just fingers, which was a much neater look than slots for screwdrivers. Stainless Steel Has Become More Common in WatchmakingIt was inexpensive but difficult to machine. Delicate texture like a coin edge bezelThe decagonal bezel didn’t last long as a design element, so Taubert returned to a two-piece construction in which the dial and movement were attached from the back, with an inner cover securing the movement under the crystal, and the caseback screwing down to keep everything in place.

The decagonal case with a cork-sealed crown was Taubert’s greatest achievement, and has been widely adopted by Mido, Movado, and even fellow Holy Trinity members Vacheron Constantin and Patek Philippe. The Patek Philippe 1463J in solid 18k gold also uses this case in chronograph form, and still bears Borger’s “FB” stamp on the caseback, as well as many Calatrava models up until 1965. This is interesting considering that Borger’s decagonal bezel was phased out in the 1930s, a time when it was becoming more popular in the 1940s.Audemars Piguet Royal OakThe octagonal bezel has been extended by 40 years.

The late 1950s and 1960s saw an unprecedented rise in the commercialization of scuba diving. Diving watches are now a consumer preferenceMany Swiss brands had a monopoly on waterproofing technology, not just the Navy’s special tools. Many of the early patents had already expired, so “waterproofing” technology became a bit of a free-for-all between hundreds of Swiss brands jumping on the skin diver bandwagon. Of course Rolex played a big role with the Oyster case from the ’20s onwards, but the story of the Oyster is well known. Taubert supposedly liquidated the company in 1972. Different Situations and the Quartz CrisisVulcanized rubber O-ring gaskets and piston-sealed crowns allowed the company to produce 1,000-meter diving watches, and Taubert’s largest product was no longer important. Still, it might not have come to fruition without the ingenuity of Borgel and Taubert in the first few decades of the wristwatch.