Buffy Acacia

In the world of high complications, the minute repeater is often prized above all others. Some may prefer the practicality of a perpetual calendar or the visual allure of a tourbillon, but hearing the soothing chimes of a small mechanical movement warms the heart of everyone. Minute repeaters are among the most difficult complications to both design and manufacture, and there are plenty of them on sale on AliExpress and other sites. Surprisingly Affordable Perpetual Calendars from Manufacturers Like Frederique ConstantApart from the obscure pocket watches, it’s hard to find a good deal on a minute repeater, and even then they cost in the four figures. How did this happen?

Measuring Time Throughout History The concept of time was much more fluid in those days than we understand it today, and visual representations of time such as clocks were not always important. Water clocks were used for thousands of years, and even the first clock with gears (invented by Archimedes in the 3rd century BC) was a cuckoo clock that supposedly chimed. Clearly, sound and the way of reading time were strongly linked from the beginning. It was not until the 12th and 13th centuries that fully mechanical clocks (then called horlogium or horloge) were invented, replacing the water clocks for the same purpose. As European religions developed more strict rituals such as canonical hours, it became necessary for churches, town squares and monasteries to ring bells at the appropriate times to call citizens to prayer. Even the word “clock” itself comes from the Old Irish word for bell.

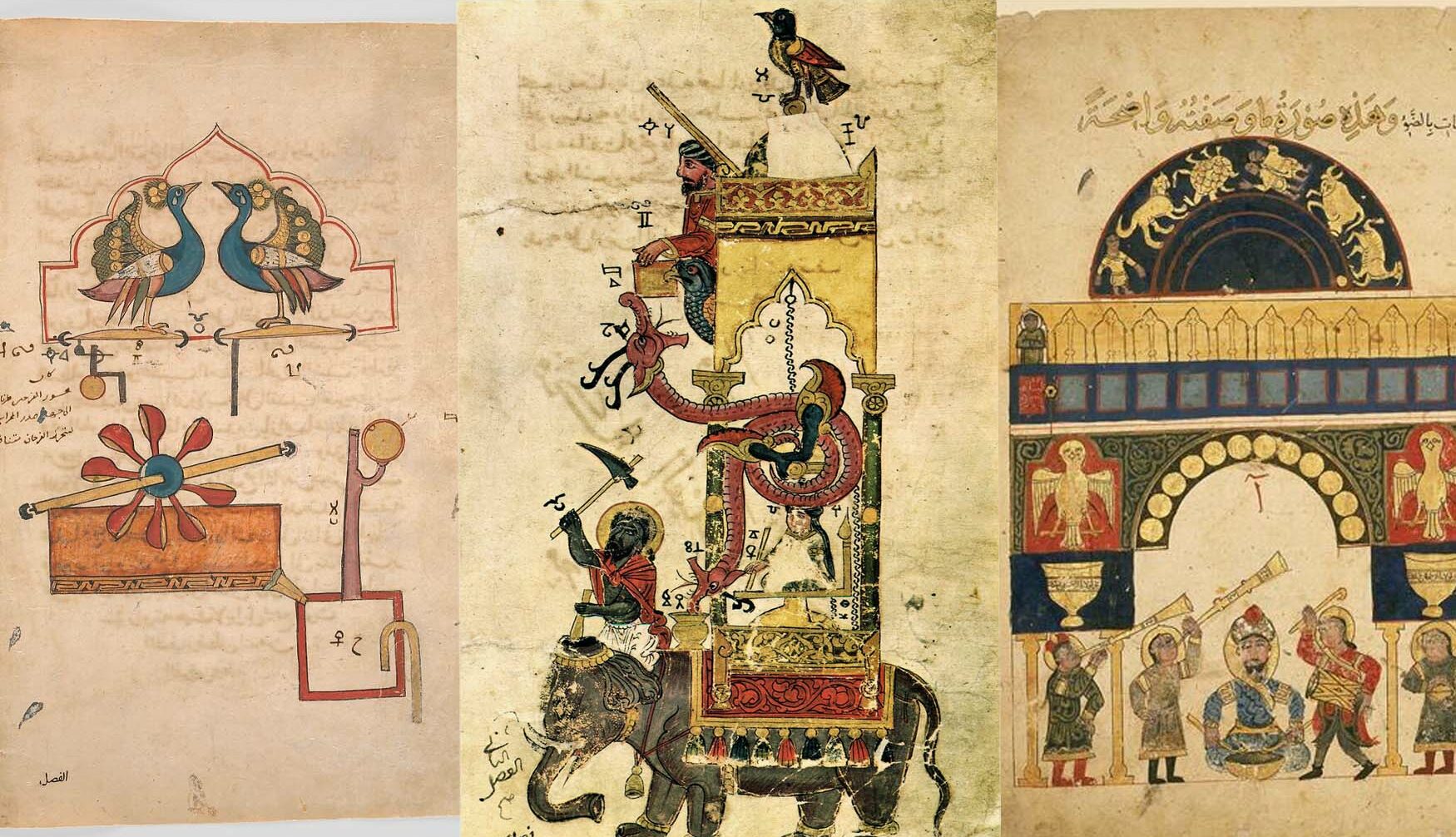

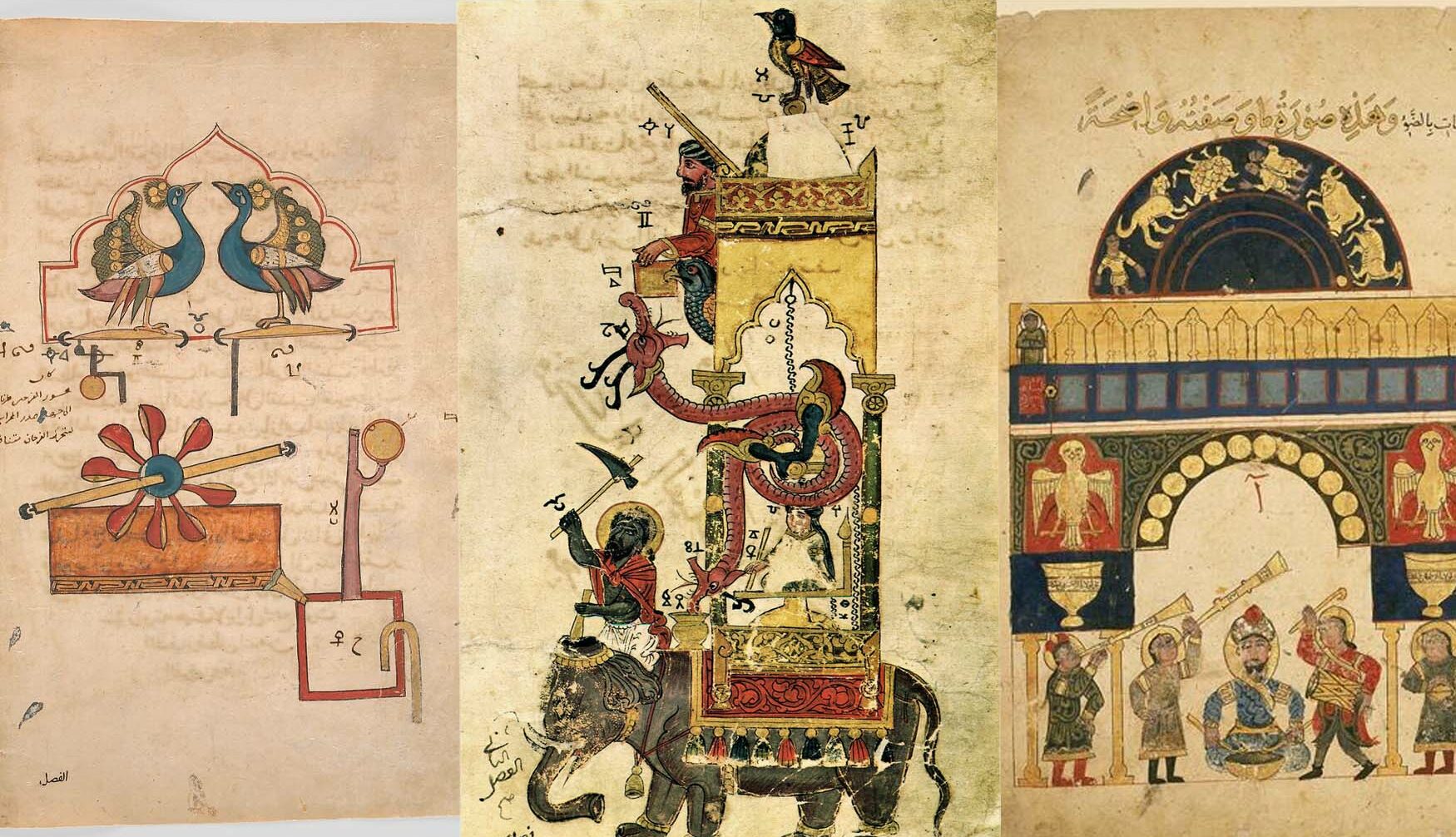

It didn’t take long for medieval engineers to start showing off their clocks, and they became extravagant. The Mesopotamian Islamic polymath Ismail al-Jazari was something of a spiritual successor to Archimedes, and in addition to designing a variety of clocks, he developed complex programmable automata, human and animal figures, as early as 1206. He even created an automated waitress that could dispense drinks from an internal cistern, a very advanced concept in robotics. When the technology made its way to the West, to Italy, France, and England, huge and expensive clocks were made, with astronomical dials that could show the time on multiple systems at once, or clocks that could show all the prayer times, making it necessary to employ full-time timekeepers. The more modest and less wealthy regions were lucky to get a dial with hands, but clocks still had a role because they rang bells.

Aside from all the astronomical, astrological and automated bells and whistles, striking clocks were still relatively simple. All that was needed was a cam attached to a shaft that rotated once every hour. The cam would raise a hammer and drop it onto a bell. In the 14th century, tower clocks were built all over Europe and count wheels were devised so that the clock would strike the exact number of hours rather than just once per hour. The difference between a striking clock and a repeater is that a repeater can chime on demand, rather than at 10 minutes past the hour. At some point in the 17th century, the rack and snail mechanism was invented, simplifying the process and making striking more reliable. This technology was utilized by priest and inventor Reverend Edward Barlow in 1675, who created the first repeater clock.

Barlow’s invention allowed repeater watches to chime the hours and quarter-hours on request at any time, just as they do today. There are several variations of this system. A. Lange & Söhne digital repeaters, etc.but the basic concept has remained the same for centuries. Given that pocket watches became popular among royalty and aristocracy within the past century and a half, repeater wristwatches began to appear. Edward Barlow and his competitor Daniel Quare both claimed to have invented the repeater pocket watch in the 1680s, but James II intervened. He asked them both to make a repeater wristwatch in 1687, which was then examined by council and Daniel Quare was granted a patent. The main difference between the two is that Barlow’s watch had two buttons, one for the hours and one for the quarter hours, which had to be pressed simultaneously. Quare’s watch used a single pin that worked for both.

Over time, repeater clocks and wristwatches were developed by watchmakers around the world. Religion no longer held such a large influence over the inhabitants of large cities, so chiming clock towers became more of a curiosity or a public service than a functional means of calling to prayer. Bells were replaced by wire gongs, which were more compact and used the case itself as a resonating chamber, emanating a richer tone and volume. However, wire gongs were always expensive, and with the rise of the middle class and the widespread use of gas lighting in the streets in the 18th and 19th centuries, the elite began to favor pocket watches over watches for the masses. There were even attempts to make repeater watches more affordable by not using gongs at all, but instead striking a hammer into the case and feeling the silent vibrations in the palm of the hand.

It appears that London watchmaker John Ellicott was the first to produce a watch capable of displaying all hours, quarters and individual minutes in large numbers around 1750. The legendary Abraham-Louis Breguet was the first to opt for gong springs rather than bells in 1783, and gong springs have been used ever since. From then on, innovations were fairly subtle, and came and went in the same way that pocket watches moved to the wrist.

Here’s how most minute repeater watches, from the late 18th century to today’s grand complications, work: The slider or pusher on the side of the case must fully engage to prevent damage to the mechanism. If it’s not fully engaged, nothing happens to protect the movement. As the slider or pusher moves, the teeth on the rack count out the hours, quarters, and minutes currently shown on the dial, and determine the chimes. This action also winds a tiny mainspring dedicated to the repeater mechanism, so the watch can’t be accidentally damaged by losing power prematurely. Next, a hammer strikes two gongs. Usually, the hour begins with a low tone, followed by two strikes, one high and one low, to indicate the quarter-hour. Finally, the remaining minutes are counted out with a high tone. For example, the time 4:38 sounds four low tones, two high low tones, and eight high tones.

As we have already learned, minute repeaters are not just complicated because they have more parts. They are also difficult to make because it is easy to make mistakes and there is little room for the parts to be the wrong shape or size. A properly made minute repeater should be the epitome of perfection, especially in a case as small as a wristwatch. Some digital and quartz watches attempt to replicate the effect of a minute repeater, and some of them are quite fun, but an electronic beep cannot replicate the romance of a physical gong chiming from a mechanical caliber.