Borna Bosniaks

It’s no secret that we at Time+Tide love Seiko, and that goes for the majority of watch enthusiasts around the world. As we enter the 2000s, much of this love is due to the brand’s unique positioning to offer great value across a wide range of price points. While you’d be hard pressed to find a decade since the brand’s inception that hasn’t produced some iconic timepieces, the 1960s stands out as a time when Seiko truly dominated in multiple areas. Following the renaissance of tool watches in the 1950s, the ’60s was all about advancements in movement technology, whether mechanical, quartz, or electric. But for Seiko, it was also about luxury. Until the early ’60s, the brand’s sub-collections were not as integrated as they are today, and none of them stood out as the best models Seiko had to offer. That all changed in 1960, heralding the beginning of an era of dominance. Let’s see what happened.

Grand Seiko – Japan’s First Luxury Wristwatch

Let’s go back a little further than 1960. In the years prior, Suwa Seikosha introduced three important collections: the Marvel in 1956, the Lord Marvel in 1958, and the Crown in 1959. The Marvel was the first watch that Suwa Seikosha produced in-house, dating back to the days when they were competing with their sister company Daini. This rivalry continued into the late 1950s, with the Daini Chronos and then the famous Suwa Lord Marvel. The Lord Marvel became the basis for the more elegant Crown. All of these had their own merits and were incrementally upgraded with each new model, with the late 1959 Seiko Crown Special model bearing a striking resemblance to the Grand Seiko First.

In 1960, Seiko decided to take the caliber 341 from the Crown Special, upgrade it with a fine regulator and two barrel jewels, and unify everything under the Grand Seiko model name. The result was the Grand Seiko J14070, featuring an embossed logo. This chronometer was the first Japanese chronometer certified by the long-named Swiss Watch Market Regulatory Agency. The Suwa-made 3180 caliber had an accuracy of +12/-3 seconds per day and a power reserve of 45 hours, and its special performance was indicated by an eight-pointed star on the dial.

However, the majority of Grand Seiko Firsts were in 14K gold cases, and Seiko was still competing with the larger Swiss manufacturers. In addition to excellent chronometer performance, Seiko cemented its position as a luxury watch with a very small number of platinum-cased Grand Seiko First variations. These are so rare that even Seiko itself cannot confirm the exact production date or number. However, this watch established Seiko’s reputation as a capable manufacturer of truly luxury watches for the first time.

Over the next decade, Daini Seikosha again voiced its opposition to Suwa’s Grand Seiko, creating the King Seiko as a counter-measure. An entire article could be written about the numerous Grand Seiko (made by both Daini Seikosha and Suwa) and King Seiko models made over the years (including the iconic 44GS, which was developed from the 44KS King Seiko), but the pinnacle of this competition was undoubtedly the VFA models. With an accuracy of +/- 1 minute per month, the best Very Fine Adjusted movements of the late 60s could rival Grand Seiko’s latest mechanical movements.

Speedtimer 6139: The First Automatic Chronograph

While Seiko’s two big factories were trying to outdo each other and the Swiss in producing ultra-precise chronometers, one particular department at the Suwa factory was hard at work creating a world first. In 1964, the Seiko Crown Chronograph hit the market as Japan’s first chronograph. It was developed by Toshihiko Oki. The success of the Crown Chronograph at the 1964 Olympics led Oki to ask him to design a new automatic type, and so the 61 series was born. At the same time, people in Switzerland had similar ideas. A Swiss consortium consisting of Heuer Leonidas, Breitling, Buren Hamilton, and Dubois Dépraz were working on a modular micro-rotor-driven chronograph called the Chronomatic, while Zenith was independently developing the movement that would become the “El Primero.”

Now a part of history, Zenith first unveiled its invention to the world in January 1969, just two months before the Chronomatic. According to internal Seiko reports, the 6139 was scheduled to be unveiled in May, but that doesn’t tell the whole story. Over the past 50 years, there have been several watches with the 6139 that have serial numbers dating back to January 1969, the year Zenith unveiled the movement. Additionally, some 6139 dials were produced as early as October 1968.

So who won? Actually, it doesn’t really matter, for a few reasons. First, it’s stories like this that make the watch so interesting. And the fact that the 6139 is still so undervalued in the larger collector community means that the average collector like me can actually afford one. Sentimentality aside, the technical superiority of the 6139 is evidenced in its construction. Oki redefined the vertical clutch mechanism for this watch, which became a staple of luxury chronographs and helped create Frederic Piguet’s 1185 chronograph, which in turn became the basis for numerous movements from Audemars Piguet, Vacheron Constantin, and Blancpain.

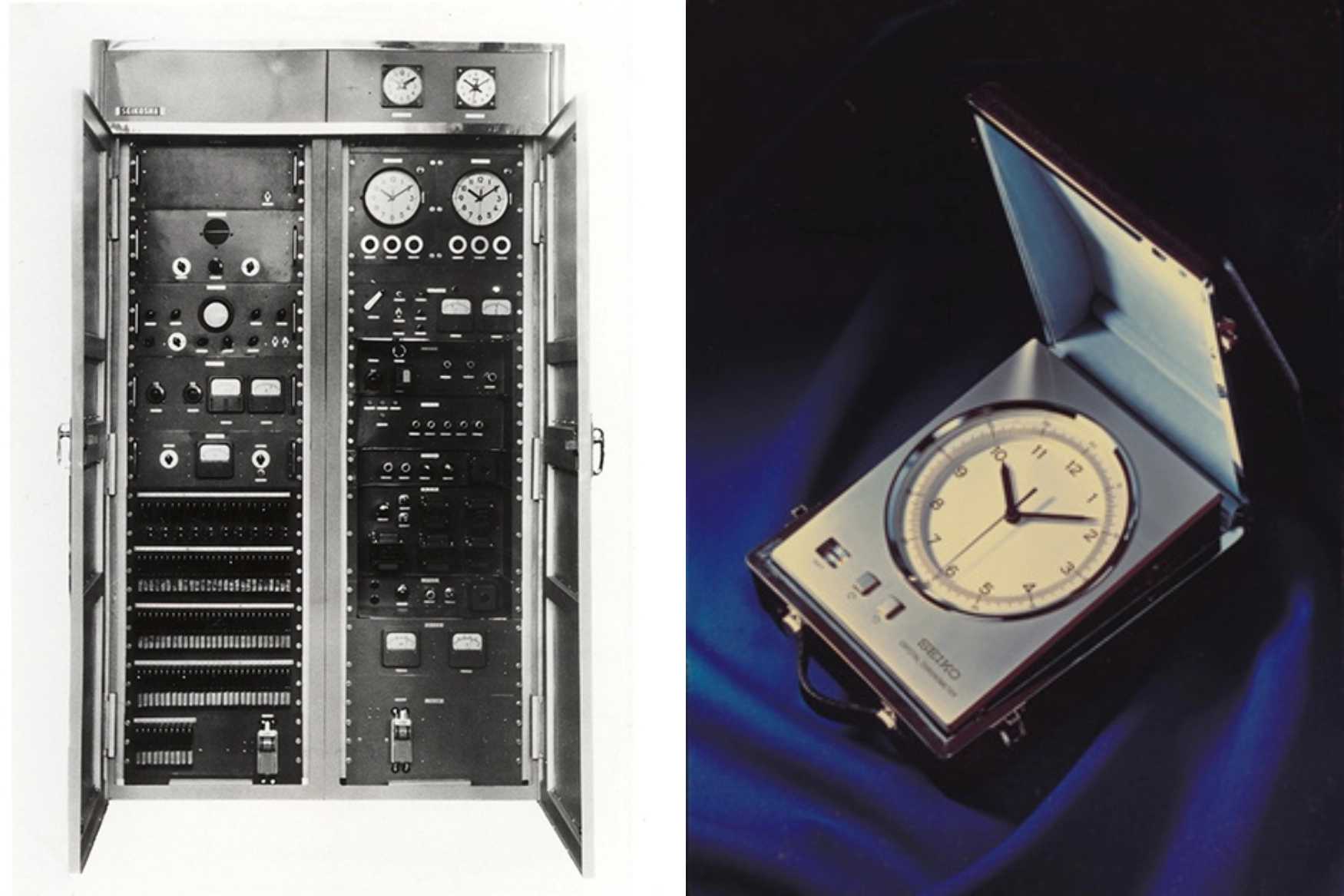

Astron: The First Quartz Watch

Of course, we come to the big event at the end, and perhaps the biggest turning point in the history of watchmaking thought. On Christmas Day 1969, Seiko introduced the Astron 35SQ. Manufactured at Suwa Seikosha, it cost $1,250 (equivalent to about $11,000 in today’s money) and its Seiko 35A stepping motor movement was accurate to within +/- 5 seconds per month. By comparison, today’s everyday mechanical watches are expected to be accurate to within 20 seconds per day.

Because integrated circuit technology had not yet reached a satisfactory level, these movements featured hand-soldered components and were the result of a decade-long project that began with miniaturizing closet-sized quartz watches. Though often overlooked, attempts such as the CEH Beta 21 and the Longines Ultra Quartz (actually the first quartz watch) were simply inferior to Seiko’s technology. Naturally, this resulted in the start of the Quartz Crisis, which changed the paradigm of fine watchmaking forever.